As regards the science of astronomy: at the beginning of the eighteenth century the heliocentric theory was generally considered self- evident. Only an empirical demonstration that would validate the theoretical accomplishments of Kepler (1571-1630) and Newton (1642- 1727) was lacking. Standard astronomical history still holds and teaches that it was James Bradly (1692-1762) who found “the first experimental proof that the earth has a yearly motion, and that Copernicus was right.”

Careful analysis of the

relevant data, however, shows that

this is not true at all, but that on

the contrary, Bradley's so-called

”aberration of star light” gave the

first experimental disproof of the

heliocentric hypothesis. To recall

to mind the bare facts: in December

1725 James Bradley and

Samuel Molyneux began a

prolonged observation of the star

Gamma Draconis, which passed

almost vertically overhead at their

location. For their observations

they fixed a telescope to a chimney stack of the Molyneux house in the

hope of detecting the eagerly sought-after parallax, thus proving at long

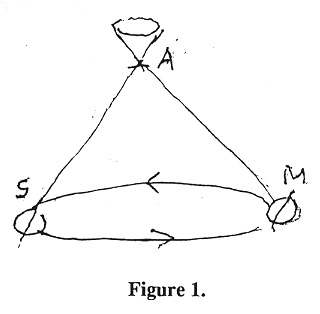

last the Copernican theory. Substantially correct, but simply stated, the

matter is this: if indeed the earth moves in its orbit around the sun, then

the place from which we observe the stars will be continually changing.

Therefore, we shall see a nearby star as moving in a small circle against a

background of more distant stars (see Figure 1). What is more: looking at

such a nearby star A from point M in March, and point S in September,

and knowing the distance SM to be about 3x108 km, we can by means of

triangulation obtain the distance to A.

Careful analysis of the

relevant data, however, shows that

this is not true at all, but that on

the contrary, Bradley's so-called

”aberration of star light” gave the

first experimental disproof of the

heliocentric hypothesis. To recall

to mind the bare facts: in December

1725 James Bradley and

Samuel Molyneux began a

prolonged observation of the star

Gamma Draconis, which passed

almost vertically overhead at their

location. For their observations

they fixed a telescope to a chimney stack of the Molyneux house in the

hope of detecting the eagerly sought-after parallax, thus proving at long

last the Copernican theory. Substantially correct, but simply stated, the

matter is this: if indeed the earth moves in its orbit around the sun, then

the place from which we observe the stars will be continually changing.

Therefore, we shall see a nearby star as moving in a small circle against a

background of more distant stars (see Figure 1). What is more: looking at

such a nearby star A from point M in March, and point S in September,

and knowing the distance SM to be about 3x108 km, we can by means of

triangulation obtain the distance to A.

Now Bradley found that Gamma Draconis indeed does describe a small circle with a radius of 20.5 seconds of arc (20”.5). The problem facing him was how to explain this phenomenon. Did it indeed result from the earth's revolution about the sun, and hence relative to the array of fixed stars? That is, did it show the parallax he had hoped to find or was the motion caused by the sun and stars circling with respect to an earth “at rest?” Bradley was forced to opt for the first alternative, but then had to reject it; for Gamma Draconis did not circle against the backdrop of stars, but all the stars joined in the motion which would imply that they were all at the same distance from earth. In other words, to accept the phenomenon as a parallax would mean re-introducing the discarded medieval concept of a Stellatum, a gigantic shell of stars centered on the sun which revolves about us. Since this was considered to be impossible, another interpretation of the observational facts had to be found. The circlets were decidedly not offering parallaxes, but what, then, did cause them?

After pondering the problem for a time, so the story goes, Bradley invented the correct interpretation in 1728 during a sailing trip on the Thames. In doing so, he thought he had solidly established the truth of the Copernican-Newtonian synthesis by means of what he called the ”aberration of starlight.”

Raindrops and stovepipes

The common misconstruction often given is that of a man walking in the rain with a straight stovepipe. “If the stovepipe is held vertically,” thus a well-known textbook, “and if the raindrops are assumed to fall vertically, they will fall through the length of the pipe only if the man is standing still. If he walks forward, he must tilt the pipe slightly forward, so that drops entering the top will fall out of the bottom without being swept up by the approaching inside wall of the pipe…. Similarly, because of the earth's orbital motion, if starlight is to pass through the length of a telescope, the telescope must be tilted slightly forward in the direction of the earth's orbital motion.” The speed of light is about 10,000 times that of the earth. Hence the angle through which the telescope will have to be tilted forward, if Bradley's explanation fits the facts, will be 20”.5. That tallies with the angle he observed, and thereby we are forced to conclude that Copernicus has the right sow by the ear!

But are we? Well, not totally! Logically considered this conclusion uses the invalid theoretical syllogism, the modus ponendo ponens. If situation P is the case, we agree, then we shall observe the phenomenon Q. Now, indeed, we observe Q. Does it therefore follow that P is the factual state of affairs? By no means necessarily, for Q may be caused by a variety of other circumstances. As one of my textbooks of logic remarks: “We shall have frequent occasions to call the reader's attention to this fallacy. It is sometimes committed by eminent men of science, who fail to distinguish between necessary and probable inferences, or who disregard the distinction between demonstrating a proposition and verifying it.”

The long and the short of it is that this heliocentric corollary does not bind us until it has been duly verified. That verification, logically unbeatable, was suggested by Ruggiero Guiseppe Boscovich (1711-1787). The performance of his proposed decisive experiment was deemed superfluous and unnecessary. Two plus two equals four, and the earth races around the sun—those are truths beyond reasonable doubt. Not until one and a half centuries later did new theoretical developments make it advisable to affirm assurance doubly sure by buttressing the Copernican conviction with Boscovich's verification of Bradley's exegesis. And thereby hangs a tale!

The point is this: Bradley's 20”.5 angle of aberration depends on the ratio between the speed of light and the orbital velocity of the earth. The latter, Boscovich reasoned, we cannot change; but the former we are able to reduce by means of observing the stars through a telescope filled with water. This will slow down the light, and consequently increase the angle of aberration. A water-filled telescope will thus have to be tilted more than an air-filled one.

Enter Airy

In 1871 G. B. Airy (1802-1892) implemented the verification of Bradley's aberration hypothesis proposed by Boscovich. As already noted, if the experiment indeed would show a larger aberration then this hypothesis would have been logically and irrefutably verified. Its modus tollende tollens logic by denying the consequent would also definitely disprove the geocentric theory of an earth at rest. Of course, Airy's water-filled instrument did not deliver the desired proof of the Copernican paradigm. Agreeing with somewhat similar tests already performed by Hoek and Klinkerfusz, the experiment demonstrated exactly the opposite outcome of that which had to be confidently expected. ”Actually the most careful measurements gave the same angle of aberration for a telescope with water as for one filled with air.

To say that in fine there was the devil to pay is not an overstatement, even when taken literally. Since the earth, as every right-thinking person is supposed to know, goes around the sun, it had to be possible somehow to explain away Airy's failure and to affirm Bradley's truth. One approach to do this stood in readiness. By means of Fresnel's so-called ”dragging coefficient,” the appearances could be saved. “It is, however, possible generally to prove Fresnel's theory entails that no observation whatsoever enables us to decide whether the direction in which one sees a star has been altered by aberration. By means of aberration one therefore cannot decide whether the earth is moving or the stars; only that one of the two moves with regard to the other can be established.

This note very helpful, ambiguous escape-hatch from an ”unthinkable” truth did, however, not have a very long life. In 1887 Michelson and Morley's once-and-for-all experiment to confirm the heliocentric creed turned out, as is well known, to be a dismal failure. Not only did it demonstrate an earth virtually at rest in omnipresent aether-space; the outcome also served “entirely to refute Fresnel's explanation of aberration.”

It goes without saying that neither one thing nor the other caused the

astronomers, if even for a few moments, to consider a geocentric solution.

The desperately stubborn search for the unfindable went on. Nonetheless,

it is out of order to elaborate here on the successive follies of

Lorentz, Poincaré, Einstein, and now even Pope John II, to undo the truth.

Their forlorn hopes to establish the veracity of the earth circling the sun

have ultimately driven them towards a no-win situation. Their efforts

have again landed the theorists in a position offering them something not

unlike the placebo that Fresnel could present to Airy. Nowadays the

high-priests of science swear by Einsteinian relativity, according to which

it is theoretically six of one and half-dozen of the other whether we

profess that the earth orbits the sun or the sun orbits the earth. “We know

now that the difference between a heliocentric and a geocentric theory is

one of relative motion only, and that such a difference has no physical

significance.” For the logically binding demonstration that this is a total

fallacy, and that the earth is indisputably unmovable and posited at the

centre of the created heaven, I refer you to my newest book.1 Here I only

occupy myself with Bradley's fictitious “stellar aberration.” It stands to reason that van der Waals looked askance at the idea of

stars moving with respect to the earth. For everyone who believes in

Copernicus—the history of astronomy after 1543 shows2 it!—cannot escape

from extrapolating a universe with countless randomly dispersed

galaxies and stars, and other solar systems. Nor can he shy clear of an

earth, which in such a context is, strictly speaking, not worth mentioning.

”For why would the stars describe this circular (or elliptic) orbits, which

moreover would be all of the same size? The earth remains in her orbit

because of the sun's attraction, but what would keep the stars in their orbits?

And also the equality of all orbits, in size as well as in phase

traversing them, strongly suggest that there has to be a common explanation

for the aberration of the different stars.”

That common explanation exists. It can be shown to be the only one

possible, but has been wishfully overlooked since 1729, and more inexcusably,

since 1871.

The gedankenexperiment2

To begin with: analogies are bent on elucidating a difficult subject

matter by means of easily understood comparisons. What light intrinsically

is, for instance, we neither know nor can know. At bottom only he,

who created it ex nihilo understands it. For the purpose of illustrating experiments

and theories in which this electromagnetic phenomenon plays a

part, expositors for convenience's sake, make use of two different

similes. They are the “rain” and the “sound” analogies. The first one

conceives light to consist of photons, i.e., minute “energy packets,” which

then can be compared with raindrops, and move as such through

whatever space is and contains. The second views light as a vibration

phenomenon, as comparable to sound waves, the front of which

propagates through it. Be this as it may, light rays travel through space in

straight lines. A telescope trying to catch the light emanating from a distant

star has to be positioned exactly in the line of sight of the observer

aiming to have that point source in his instrument's crosshairs. Only

when this is done will the photons or the waves' fragments correctly enter

his eye and be perceived. It is not possible to behold electromagnetic

radiation from the side. When two people are looking at the moon,

neither of them can see the rays entering the eyes of the other one. Telescopes

cannot bend the light of point sources to make them go straight

down from lens to eyepiece, or unscientifically expressed, with a spy-

glass you cannot look around a corner.

To stress the crucial importance of these considerations for a logically

convincing scientific analysis of Airy's failure, I necessarily resort to a

gedankenexperiment. First of all, the stove pipe of the generally accepted

explanation is not applicable to the matter at hand. The comparison is inadequate.

The air inside the pipe and moving along with it disturbs the

free fall of the incoming raindrops. The situation is not so simple as that

analogy suggests. For a better approximation I prefer the picture of a

man equipped with a more substantial, “open” tube of wire netting. Furthermore,

I must imagine a calm, rainy day, and then put our observer

outside, instructing him to hold his “telescope” in such a manner that the

raindrops always travel straight through that crude device. That is to say,

in the case of star-gazing, the telescope has to be aligned with the

observer's line of sight.

So long as he is standing still, and while there is no wind, this is

easily done; he just has to hold his simple tool in a vertical position.

When a wind springs up, however, our man has to tilt his tube against its

direction at an angle determined by the ration of the rain cloud's velocity

to the rate of free fall of the rain. That is in reality the ratio of the star's

velocity to that of light. And if he in some way or other is able to reduce

the resultant velocity of the rain drops traveling through his makeshift instrument,

the angle of tilt will remain the same. The rain does not enter

the pipe at an angle to that pipe's direction. The drops travel through it

exactly the way they did when there was no wind. Or, changing from an

imperfect analogy to observational reality, if a water-filled telescope is

focused along the line of sight to the star, then the photons and their wave

fronts are not subject to refraction. There is in that case no change of

direction. We “see” the star at the place where it was when the light left

it. I am fully aware that the mind of modern men will find it difficult, if

not impossible, to accept this conclusion. It makes havoc of everything

the cosmogonists and cosmologists have assured us of since childhood.

Over against that I can point to two solid considerations seldom realized.

The so-called scientific method, now overwhelming us with extramundane

notions about black holes, cosmic strings, billions of light years, and

what not, offers us nothing more than possibilities. True, to devise

theories that more-or-less cogently explain unreachable far-off

phenomena, is a game we can play ad infinitum. But, affirms Stephen W.

Hawking: “Any physical theory is always provisional, in the sense that it

is only a hypothesis: you can never prove it.” Or, to quote another scientific

eminence, Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882-1944): “For the

reader resolved to eschew theory and to admit only definite observational

facts, all astronomical books are banned. There are no purely observational

facts about the heavenly bodies. Astronomical measurements are,

without exception, measurements of phenomena occurring in a terrestrial

observatory or station; it is only by theory that they are translated into

knowledge of a universe outside.”

As a statement of fact, post-Copernican astronomy is, insofar as truth

is concerned, just as empty of substance as evolutionary theory. The Darwinists

cannot go back in time to check the reality of their confident as

sertions. The cosmologists are unable to verify their prognostications in

situ.

Be this as it may, such an earth-centered explanation of the available

data does, of course, not prove the geocentric theory. Logically, the existence

of another, even a heliocentric, version is thereby not excluded. In

any case, whatever the correct equation, it will have to account for the

fact of the 20”.5 angle of Bradley's telescope and, consequently, for the

30 km/sec velocity of either the earth or the sun and all stars. And it is

this “either-or” cast that makes it possible to refute the specious

”aberration of starlight” by means of an indirect demonstration: a

demonstration which does not only overthrow the Copernican theorem,

but also exposes a fatal flaw in its Einsteinian offspring, now beguiling

the world.

As to the latter, in the ruling conception of space, all motion is held to

be relative. If, however, of two bodies in that space, the on—here,

Gamma Draconis,— is a light source, and the other—here the

earth—harbors an observer, then this is simply not true. In case the light

source moves relative to that observer, he will be able to align his telescope

with his unaided eye's line-of-sight. If to the contrary, he moves

relative to the light source, he will be hampered by “aberration.” True, at

low speeds the necessary tilt of his tool may be too small to be observable

and taken not to be there, but it always exists, even if I only move my

head when looking at a lamp in front of me. For instance, if the earth

would move at the speed of sound (circa 1200 km/hour) the required tilt

would be only 0”.2, and an observer and his instrument revolving at a

velocity of 100 km/hr would cause a 0”.02 angle which, for 10 km/hr,

will shrink to 0”.002. We are, however, presumedly orbiting the sun at a

velocity of more than one hundred thousand km/hr, and then the aberration

factor is large enough to prohibit its own observation by means of a

telescope able of measuring seconds of arc.

To show this, let's return to my gedankenexperiment where we imagined

an observer walking through the rain. The first circumstance,

which this view forces us to realize, is that the telescope must be tilted at

such an angle that the raindrops remain untouched by it. Or the photons

can, after traversing the instrument, unimpedely proceed in the direction

they had before entering it, which is to say that for an unaided eye not

clamped to the ocular but posited in the line-of-sight to the star, the telescope

might just as well not have been there. But for a man at the

eyepiece, things are quite different. The trajectory of the ray emitted by

the far-away point source, Gamma Draconis, may enter exactly at the objective,

it egresses obliquely to the plane of the ocular. That is, the star

will not be seen by the astronomer manning the instrument. Aligning

your telescope with your line of sight is not the same as aligning your line

of sight with your telescope. The first is easily done, the second is impossible.

Stellar aberration la Bradley has telescopically never yet been

observed. In short, the convinced Copernican Boscovich proposed the

right thing for the wrong reason. He supposed that a water-filled telescope

would conclusively prove the heliocentric theory. But to translate

a Dutch expression: “with that crooked stick, Airy made a straight hit.”

His experiment was powerless to show that Gamma Draconis' circular

movement was only apparent. Shortsightedly forgetting the fact that telescopes

cannot bend radiation to look around corners, he affirmed on the

contrary that stars really describe orbits equal to that of the sun.

What the fictitious “aberration of starlight” de facto shows is the

parallax Bradley and Molyneux were searching. But it is a geocentric

and not a heliocentric one. Our telescopes actually follow the stars in

their courses, all of them depending on, and concordant with that of the

sun orbiting the earth. Which sun is at the heart of the stellatum, very

slowly precessing around that Great Light.

All the foregoing, I realize, the reader will not be inclined to accept or

take seriously. The only thing I can do is to reinforce the truth of it with

the help of yet another indirect demonstration. It shows how it makes no

sense to be a Copernican and at the same time to adduce the 30 km/sec

orbital velocity of the earth in explaining the stars' “aberration.”

If we accept the Copernican viewpoint and its unavoidable extrapolations

with regard to the structure of the universe, we have to accept the

consequences. Then we cannot hold on to the picture of a simple sun-

centered cosmos, of which not even Newton was fully convinced, but

which Bradley and Molyneux took for granted. Today the astronomers

assure us that our Great Light is only an insignificant member of a spiral

Milky Way galaxy, containing billions of stars. Our sun flies at a speed

of about 250 km/sec around the center of this system. And that is not all,

the ruling cosmology also tells us how the Milky Way itself whirls at

360,000 km/hr through the space occupied by the local group of galaxies.

Now all these imposing particulars are theoretically gathered from observations

assuming the speed of light to be 300,000 km/sec, at least,

everywhere through our spatial neighborhood. But if this cosmological

panorama is put through its paces, there is a hitch somewhere. The

astronomical theorists cannot have their cake and eat it. If they accept—

as all the textbooks still do!—Bradley's “proof” of the Copernican truth,

then their cosmological extrapolations of that truth clash with a not-yet

developed simple heliocentrism; that is to say, with the model of an earth

orbiting a spatially unmoved sun.

The other way around, when holding on to their galactic conjectures,

they are at a loss how to account for a steady 20”.5 stellar aberration. For

in that scheme our earth, dragged along by the sun, joins in this minor

star's 250 km/sec revolution around the center of the Milky Way. If, for

instance, in March we indeed would be moving parallel to the sun's motion,

our velocity would become 250+30 = 280 km/sec, and in September

250-30 = 220 km/sec. The “aberration of starlight,” according to post-

Copernican doctrine, depends on the ratio of the velocity of the earth to

the speed of light. As that velocity changes the ratio changes. Hence

Bradley's 20”.496 should change, too. But it does not. Therefore, there

is truly a fly in this astronomical ointment, paraded and promoted as a

truth.

”Not true,” the theorists will object, “such out-dated reasoning in a

space knowing place cuts no ice with us. Relativity has no difficulty with

that kind of supposed contradiction.” I dare to differ. Their Einsteinian

panacea, foreshadowed by the prevarications of Fresnel's “We cannot

decide,” Lorentz's “We cannot measure,” and Poincaré's “We cannot observe"

is mere eyewash. Consider: according to the ruling paradigm, it

makes no physical difference whether I declare either the earth to move

with respect to everything else at rest, or declare the earth to be at rest

with respect to sun and stars moving around. Starting from an earth at

rest, and hence aberration being absent, then whatever the truth, the annual

standard size circlets of all the stars are real and not caused by our

29.8 km/sec orbital velocity. Instead of a heliocentric “aberration,” we

are confronted with a geocentric parallax, and these parallaxes being

practically the same size for all stars, these stars must be at the same distance

from us. This points to the existence of the stellatum of old.

This will be judged to be patently “unthinkable” or worse. Bradley's

unobservable and by Airy's failure emasculated “stellar aberration”

remains indispensable for holding on to a Big Bang and a universe expanding

into space or expanding space. Manifestly, such a post-

Copernican cosmos could not differ much physically from the pre-

Copernican one. To say that this is a difference of motion only is nonsense.

It allows me to agree with Stephen W. Hawking: “You cannot disprove

a theory by finding even a single observation that disagrees with

the predictions of the theory.” Conclusion: Einstein's cure-all cures nothing!

Assuredly,

I do not claim that the foregoing proves my modified

Tychonian hypothesis. Experimentally, however, it undoubtedly has the

soundest credentials. More than three centuries of efforts to disprove it

have already come to naught. The pseudo-heliocentric universe

popularized for the benefit of the man-in-the-street has, in fact, not a leg

to stand on. The earth-centered theory is and has been found to save all

spatial appearances.

Does the earth rotate?

The question still to be addressed is whether our home in the heavens

daily rotates with respect to the solar system and stellatum or vice versa?

A striking attribute of human thinking is, as I see it, that this thinking

cannot attain unto total relativity. Playing up to Einstein, his followers

may hold that “every object we perceive is set off by us instinctively

against a background which is taken to be at rest.” Yet motion and rest

set off against space, I hold, are not in such a psychological category.

There are foundational facts. Celestial bodies we may take to be moving

relative to one another or any preferred background. All objects, great

and small re, however, absolutely in motion or at rest with respect to

space. For space is not in motion relative to anything. It makes motions

and rest possible and definable, and there is an end of it, unless one takes

recourse to spaces floating around in higher spaces. That is, however, a

game we all can play, acentrist, heliocentrist, and geocentrist alike. If in

the universe you prefer the sun to be taken at rest, in my next-higher one I

can give the earth pride of place. But such theoretical cavorting on the

quicksand of an infinite regress is nothing to write home about. The only

space permitting us to test hypotheses experimentally and to evaluate

them logically is the three-dimensional expanse around us. Pseudo-

metaphysical proposals may be devised to evade unacceptable “flat

space” matters of fact: they carry no weight in strict empirical scientific

disputations and refutations.

As far as the latter are concerned, the denial of the earth's rotation

runs in reasoning parallel with the disavowal of our annual revolution.

To quote the late Bertrand Russell (1872-1970):

I shall not therefore conclude that the earth is at rest, because this experiment

has shown what I hoped it would show. Bradley's telescope

could not catch what he thought it would catch. In the same way, I may

be mistaken. On top of that, the “scientific method,” firmly established in

Bradley's time, is today, almost four centuries of misrule later, again acknowledged

powerless to prove anything. Until further notice I am allowed,

however, to adduce the negative outcome as a point in favor of my

thesis.3

”But all experimentalizing aside,” a reader may ask, “will it not be

difficult to win mankind back to a universe daily revolving [sic] around

us?” According to the enthroned astronomy, the earth is comparatively

no more than a grain of sand on a seashore. Even accepting the stellatum,

is it not, or does it not seem the height of folly to declare this speck to be

the pivot on which the pattern of those numberless far-away light points,

annually as well as diurnally turns?

I admit that with regard to the enormous rotational velocity we seem

to have to assign to the stellatum, this at first sight appears as a difficulty.

But allow me to ask an ontological question. “Is there endless empty

space, with somewhere in it our universe? Or is that universe a finite

”bubble” of space in absolute nothingness?” A fervent Greek supporter

of the Tychonian quest, the late Harry Kavafakis, stoutly proclaimed that

his compatriot of old, Aristotle, has been the only man ever to have an IQ

surpassing the 200 mark. Well, it is worthwhile to quote this famous

Stagirite on the matter> “Outside the heaven there is neither place, nor

void, nor time. Hence whatever is there is of such a kind as not to occupy

space, nor does time affect it.” I could not agree more. With regard to a

stellatum rotating in the metaphysical unknowable, who can measure the

kilometers when there is no space like ours and no clock to measure time

like our time?

Last and not least, in space exploration and all applied sciences needing

more-or-less astronomical input the practitioners are aware that according

to Galileo, the earth is in motion. They also know that nobody

has ever de facto shown this to be the case. Now, to start from an earth at

rest is simpler than to start from the universe at rest. Hence, leaving

theory theory, they hold on to what after all is obvious, confirmed by our

senses, and taken to be self-evident by the Book of God. 1 2 3

In order to stress the all-embracing importance of that short-

sightedness, which has been blatantly accepted for nearly two hundred

years, it may be well to cite a twentieth-century appraisal of Bradley's

and Airy's quandary by the Dutch physicist, J. D. van der Waals, Jr.

”Aberration may equally well be squared with the supposition that the

stars indeed describe circlets. And though we find the latter explanation

improbable and prefer the first, the question may arise: is it in no way

possible by means of observations to decide which of the two suppositions

is the right one?”

Suppose now that we apply these considerations to Bradley's discovery

of the annual circlet of Gamma Draconis, and to Airy's 1871

failure to clinch the truth of the heliocentric hypothesis. This parochial

sun-centered paradigm has since then been found wanting on all counts.

It cannot truly assess the great and mysterious cosmic riddle. Relativity

now rules the roost, and therefore nobody can blame me for putting it to s

good use. “Since the issue,” as Fred Hoyle formulates is, “is one of relative

motion only, there are infinitely many exactly equivalent descriptions

referred to different center—in principle any point will do, the moon,

Jupiter….” Hence I first want to evaluate Airy's data from an earth at

rest with sun and starry dome revolving with respect to us. Switching

from the analogies to the reality, it will be seen that this theoretical position

saves the appearances faultlessly. The speed of light taken to be constant

throughout the observable cosmos, the 20”.5 tilt of Airy's water-

filled telescope ruled out the earth's motion. It revealed and confirmed

that the stars of the Stellatum all run their slightly-elliptical courses with

precisely the 30 km/sec velocity still mistakenly attributed to Mother

Gea. She is the pivot on which the heavens turn!

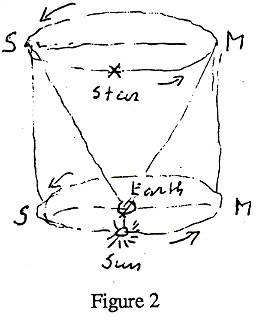

It is this geocentric parallax

which allows us to defend and

promote a comparatively small

universe, dismissing an aberration

of starlight which does not exist

(see Figure 2). Of triangle

S-Earth-M the angle at earth is 41

seconds of arc, and SM = 108 km.

By means of triangulation the distance

Earth-Star, that is the radius

of the Stellatum, can be calculated.

It turns out that, on the

average, the light of the stars

needs 58 days to reach us.

It is this geocentric parallax

which allows us to defend and

promote a comparatively small

universe, dismissing an aberration

of starlight which does not exist

(see Figure 2). Of triangle

S-Earth-M the angle at earth is 41

seconds of arc, and SM = 108 km.

By means of triangulation the distance

Earth-Star, that is the radius

of the Stellatum, can be calculated.

It turns out that, on the

average, the light of the stars

needs 58 days to reach us.

Before Copernicus, people thought that the earth stood still and that

the heavens revolved [sic] about it once a day. Copernicus taught that

”really” the earth revolves [sic] once a day, and the daily rotation of

the sun and stars in only “apparent”… But in the modern theory the

question between Copernicus and his predecessors is merely one of

convenience; all motion is relative, and there is no difference between

the two… Astronomy is easier if we take the sun as fixed than if we

take the earth… But to say more for Copernicus is to assume absolute

motion, which is a fiction. It is a mere convention to take one

body as at rest. All such conventions are equally legitimate, though

not all are equally convenient.

As I have shown above, this relativism is misleading. Space knows

place and movement rest. To declare the earth-centered view “as good as

anybody else's, but no better,” is short-sighted. If we suppose ourselves

to move with respect to the stellatum, the aberration of starlight has to be

reckoned with. For an earth at rest, it does not come into play. In principle,

Airy's experiment can be brought to bear on the quandary.

Theoretically, a water-filled telescope, installed on the equator, and accurate

enough to measure fractions of seconds of arc, can settle the matter.

For it will have to be tilted about 0”.14 more than our air-filled one

because of the earth's daily rotation relative to the stars. Whether this

test is practical, I do not know; but another experiment that convincingly

demonstrates the earth's immobility has been conducted. It was sensitive

enough to measure changes in the speed of light through space of less

than 25 m/sec. Performed at 49° north latitude, the rotational speed of the

apparatus was 305 m/sec. It registered no rotational effect whatsoever.